The strange case of Melts’ long-lost album Salicoutinäw begins in the winter of 1994. Drummer Andrew Barker, bass player Jo Jameson, and the group’s singer, guitar player, and principal songwriter Theo X had made the long haul from Atlanta to the snow-covered landscape of Minneapolis to record their full-length debut. After releasing the “667” b/w “Crusser” 7-inch single a year earlier on the Greensboro, NC label, 227 Records, the group was primed to cut the LP with 227. The label’s owner Jay Boone did the footwork, made the connections, and lined up a few days of studio time with engineer Tim McLaughlin at Amphetamine Reptile Recording Studios.

A few years earlier, the New York City-based noise rock outfit Helmet had become the subject of a major label bidding war. Ultimately, Helmet moved away from their home at AmRep to the more mainstream auspices of Interscope Records, to release their 1992 classic album Meantime. As a result of so many major labels clamoring to sign Helmet, AmRep Studios had become a well-funded, well-outfitted resource. Along the way, engineer Tim “Mac,” who also played bass with Minneapolis’ noise punk provocateurs Halo of Flies, had become a respected studio hand.

“Some of the members of the bands Today is the Day, Mickey Finn, and Godplow had all spoken positively with us about recording with Tim Mac,” X says. The Melts frontman prefers using his pseudonym when discussing the band. “We were excited to work with someone who was well-versed in the language of recording loud and noisy music.”

After all, it was the early ‘90s. Nirvana was ascending to new commercial heights after releasing 1991’s breakthrough album Nevermind. The word “grunge” was splashed across newspaper and magazine pages worldwide, culminating in a clearly defined but increasingly clichéd sound and fashion trend—the grunge look.

But beyond the mainstream’s myopic vision, an underground noise rock scene flourished, culminating in an era of sludgy, antagonistic, and guitar-heavy bands such as Cows, Unsane, Hammerhead, the Jesus Lizard, Skin Yard, Cherubs, Melvins, and more churning out raw rhythms and distortion that moved at the speed of molten lava.

The sheer sonic intensity of Melts’ thunderous rhythms wrapped in a penchant for debauched antics drew a wild, sometimes confrontational element out of the audiences who’d come to their shows.

Barker laughs when he recalls narrowly avoiding a scuffle one night when Melts shared the stage at Dottie’s with Cat Power and King Kill 33.

“We played the show and this guy got right up in my face,” Barker says. “He wanted to fight me or have me come back to his friend’s house so we could have a drum competition. He wanted to show that he was a better drummer than me. At first, I thought he was joking but it got a little intense until Jo stepped in and talked him down.”

On another night, Melts were kicked out of the Clermont Lounge for getting naked on stage and lighting a 500-count roll of Black Cat firecrackers during their set.

“The style of music we were playing wasn’t much of a genre yet,” X says. “We had a lot of good samaritans coming to us along the way telling us we were tuning our guitars wrong. The songs we recorded for the album are tuned in B. It’s low, and sound guys would come along and say things like, ‘Hey buddy, let me help you with that guitar so we can get it tuned the right way.”

In conversation, Jameson casually mentions the name Ernie Dale, pausing only for a second as X laughs. The former soundman for Little 5 Points’ fabled former music dive The Point, was well known for not putting up with foolishness of any kind.

“Ernie is great, but if you had something that Ernie deemed to be a bad sound, he wanted to mentor you out of it,” Jameson says. “He couldn’t believe that we were intentionally making these sounds.”

Stories like these, coupled with the down-tuned guitars, heart-pounding drums, and the wide-eyed crawl of songs like “Grape,” “Jackdaw,” and “Cotton Hol” earned Melts a reputation as Atlanta’s answer to sludge metal pioneers the Melvins. But the 14 songs on Salicoutinäw stamp in time a singularly creative and distinctly Southern group that defied expectations, rather than simply adhered to trends.

When promo CDs of Salicoutinäw were mailed to college radio stations the album quickly gained traction. Salicoutinäw even broke the CMJ LOUD 100 chart in 1994. But when a pressing plant failed to deliver the first pressing of finished CDs that had already been paid for, the high cost of working in the music industry in the ‘90s added up too quickly, and 227 Records went out of business. The promo CDs, featuring a primitive, last-minute cover illustration, had a greater reach than the finished product.

By the band’s estimation, maybe 100 copies of a later second pressing of the CD made it into the public’s hands. But it was too little too late. The group received boxes of CDs with the proper cover art, but any distribution 227 Records could’ve offered was long gone, and any steam the group had built up went with it.

“I was blown away by Melts the first time I saw them,” Boone says. “I also adored them as individuals—still do! That’s why I have no animosity or was ever bitter about the shortcomings of the record. I still believe they could’ve done very well, but like so many things in life, shoulda, coulda, woulda isn’t worth dwelling on too much.”

With Melts, the 227 situation was only slightly better than the fate of their Athens labelmates Harvey Milk whose self-titled, Bob Weston-recorded debut album was shelved altogether. That album finally saw the light of day in 2010 when Hydra Head pressed it to vinyl.

Melts’s debut album has remained in obscurity ever since.

“It derailed me,” Jameson says. “The tedium of working on a record—putting so much time and energy into it—and waiting for it to arrive was frustrating. Ultimately, Theo and I parted ways over it. I was pushing for us to rehearse and to play more shows. I was all of 24 years old and was a booger-eating moron. I had no idea how many roles [Theo] juggled with everything from negotiating the release to playing the music. As we’ve discussed in the last couple of years, we misunderstood what each other said,” he goes on to say. “I had quit the band in his eyes. I didn’t intend for that to happen, but whatever I said drew a line in the sand. He had so many responsibilities with this band. I was shortsighted about it. But we’re adults now, and 30 years later, I see it.”

Not long after Salicoutinäw’s botched release the lineup dissolved. Jameson and Barker joined alternative country and Americana singer and songwriter Kelly Hogan’s band to release her debut album, The Whistle Only Dogs Can Hear. Jameson also did a stint playing with Archers of Loaf frontman Eric Bachmann in the band Crooked Fingers.

Barker continued playing drums with the outsider jazz ensemble Gold Sparkle Band. He still regularly performs and collaborates with various artists around New York City.

From there, X kept Melts moving forward with new members over the years. In 2003 he moved to Fort Collins, CO where he started working with the psychedelic Americana outfit Little Darlings.

Now, 30 years later, a self-released double LP pressing of Salicoutinäw has rekindled the group’s true power and allure, pushing the music and the English language into mysterious new realms of the imagination, while planting the band firmly in the present.

Jameson and X started playing music together in 1984 under the name Saboteur. They were high school kids by day, but their nights were spent practicing in X’s parents’ basement in Smyrna, crafting a hybrid of quasi-hair metal and thrash punk. By 1988, the band name morphed into Sabotortoise while they landed gigs at Atlanta’s storied downtown venue The Metroplex, opening up for nationally touring acts including LA Guns, Faster Pussycat, and Humble Pie.

Back then, X went by the moniker Ted Sunshine–different bands get different pseudonyms.

Melts was christened in 1990 when X and original drummer Tim Jordan recorded and released a cassette tape of early material titled As Noisy As We Want To Be.

Over the years, various members cycled through the group. In 1991, filmmaker Chad Rullman who later directed Mastodon’s “March of the Fire Ants” and “Iron Tusk” videos played bass in Melts. A year later, Jimmy Bower of NOLA sludge band EyeHateGod played bass for a stint.

Jameson’s initial run with Melts started in 1992 and lasted through Salicoutinäw. In 2021 he was welcomed back into the group. Original drummer Tim Jordan also returned to the lineup.

Since his early teenage years, X’s writing style with lyrics and band names has remained somewhat impenetrable. Everything from changing the first band’s name to Sabotortoise to an album titled Salicoutinäw to belting out songs titled “Vaccua 8 #3,” “Lessie,” and “Crusser,” X sculpts a jumble of words, letters, and numbers smashed together creating a wholly new mode of communication.

While pointing to the words on the album’s original cover, which is fully restored for the vinyl release, he explains them as though they are a Rosetta Stone to understanding his mashed-up style.

“On the cover you have ‘Sao’, like the Tao, and ‘sow’ like a mother pig,” X says. “You’ve got ‘Sally’ and then you’ve got cooties! And then chicken coop,” he says before phonetically singing, “Just like the white-winged dove sings a song, sounds like a chicken/Baby coop/Chicken coop. I borrow a lot of lyrics from Michael Jackson, George Michael, Madonna, and Stevie Nicks,” he goes on to say, “but I run them through a semantic discombobulator that turns them into some fresh pudding.”

To be sure, X’s lyrics evoke an absurdist’s sense of humor that lies somewhere in the vicinity of Marcel Duchamp’s dada-esque wordplay, Naked Lunch author William S. Burroughs’ cut-and-paste techniques, the Rev. Howard Finster’s primitive folk art, and an ecstatic Southern Baptist speaking in tongues. Still, his dynamics exist in their own avant-garde funhouse of meanings. Salicoutinäw opens with “Weu know t’live must two/ Yer muther sells sunduh the blackiss/ But under won is a vacuum/ Every tin’shy.”

When spelled out, the syntax appears to be nonsense, but it all makes perfect sense to him.

“It’s kind of like, before people were referring to music as emo, this was my version of that,” he laughs. “It certainly seems to have been very therapeutic.”

Jameson chimes in, adding in a deadpan voice: “You’ve just been granted unlimited access to step inside the mind of Theo X. Be careful in there.”

X continues describing his use of language as an amalgamation of emotions, energy, and warped synapses that he channels into Melts songs.

“My brain might have developed in a way that is slightly abnormal or has some sort of organic brain damage,” X says. “I have been around heavy metals, solvents, and thinners—in railroad car quantities—my whole life. Like, 50,000 square feet at a time in the middle of July and August with no ventilation. Also, my academic interests are in language and semantics, especially within religious texts.”

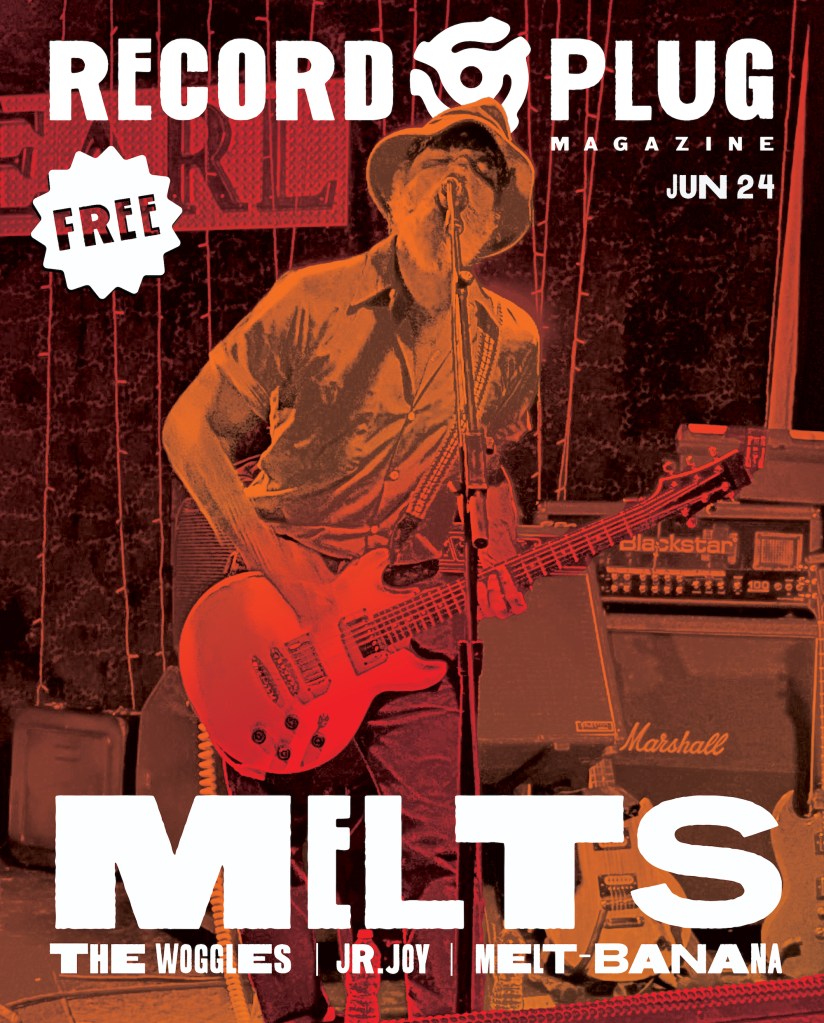

and Jo Jameson. Photo by Steve Gaiolini

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Jameson found himself listening to songs from Salicoutinäw after so many years. “I thought, ‘I really want to put a needle on these songs. Can we press just one or two copies so that I can have it on vinyl?’”

Pressing up such limited quantities of the record wasn’t feasible, but it started a conversation that brought X, Jameson, and Jordan together to play music. Their reconvening yielded a proper double LP release of Salicoutinäw. But there were hurdles to overcome before they had records in their hands. Chief among them was the artwork.

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the way to store big digital files for personal computers was on a removable 44- or 88-megabyte SyQuest drive. “It was about the size of an old 8-Track tape,” Jameson says.

They could be taken to Kinko’s, for example, where layout, design, and scanning were completed. The user would then pay for their time on the computer. The technology is long antiquated. After digging up X’s old SyQuest drive, the group’s friend, Record Plug Magazine’s Creative Director Andrew Quinn connected them with a specialist in California who was able to retrieve the files. After decades of gathering dust, everything was still in working order. Quinn led the efforts in reworking the album’s cover art and the insert, which includes a timeline of the band and everyone who was a part of it.

X, who produced Salicoutinäw made no alterations from the original recordings prior to handing them over to Morphius Records for vinyl production.

A record release party had to be booked. Barker played on the album, but Jordan is the band’s current drummer. X and Jameson delicately approached Jordan to float the idea of bringing Barker down from New York to maybe play three songs for the show. Jordan’s reply: “That sounds amazing! Let him play the whole show, I want to see that! I never saw Metls with Drew playing drums!”

As a historical document, pressing Salicoutinäw on vinyl is a necessary step in correcting the past for Melts. It also gives the group solid ground to move forward once again. They pressed only 200 copies of the LP because “We think we can sell that many and not have them lying around for years,” Jameson says.

While they don’t have new material in the works, there is a tremendous backlog of older Melts songs that have never been recorded, including a follow-up album that X wrote, called Melts Inc., which was named after X watched all the episodes the “Melrose Place” spin-off series “Models Inc.”

“Because the first one failed so catastrophically to meet its audience, we

made a pact to work through some of the older rehearsal tapes and live

recordings before we say, ‘Let’s write a new song,’” X says. “We’ve been

rekindling some of that, and there is a lot of that stuff lying around, so there

is more to come.”

This story originally appeared in the June issue of Record Plug Magazine.

If you have enjoyed reading this review, please consider donating to RadATL. Venmo to @Chad-Radford-6 or click on the PayPal link below.