Read Parris Mayhew talks life after Cro-Mags, Aggros, and ‘Chaos Magic’ (Part 1)

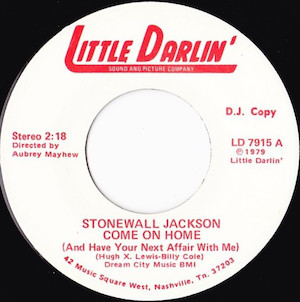

In this second part of RadATL’s interview with former Cro-Mags and current Aggros songwriter and guitarist Parris Mayhew, the conversation turns toward the influence of his father, Aubrey Mayhew. The elder Mayhew was a formidable honky-tonk and country music industry presence. In the 1960s, he worked with the budget label Pickwick Records. Later, he owned the Little Darlin’ and Certron labels. Over the years, he released hits and cult classics, such as Johnny Paycheck’s “(Pardon Me) I’ve Got Someone to Kill,” Stonewall Jackson’s “Pint Of No Return,” and even Clint Eastwood’s “Burning Bridges” b/w “When I Loved Her” single. He was also an aficionado of John F. Kennedy memorabilia. In 1970, he was the highest bidder in an auction for the Texas School Book Depository building in Dallas—the building from which Lee Harvey Oswald fired the bullet that killed President Kennedy on November 22, 1963. His influence bears a lifelong impression on Parris, whom, since his father’s passing in 2009, has fought his legal battles, working toward closing his estate.

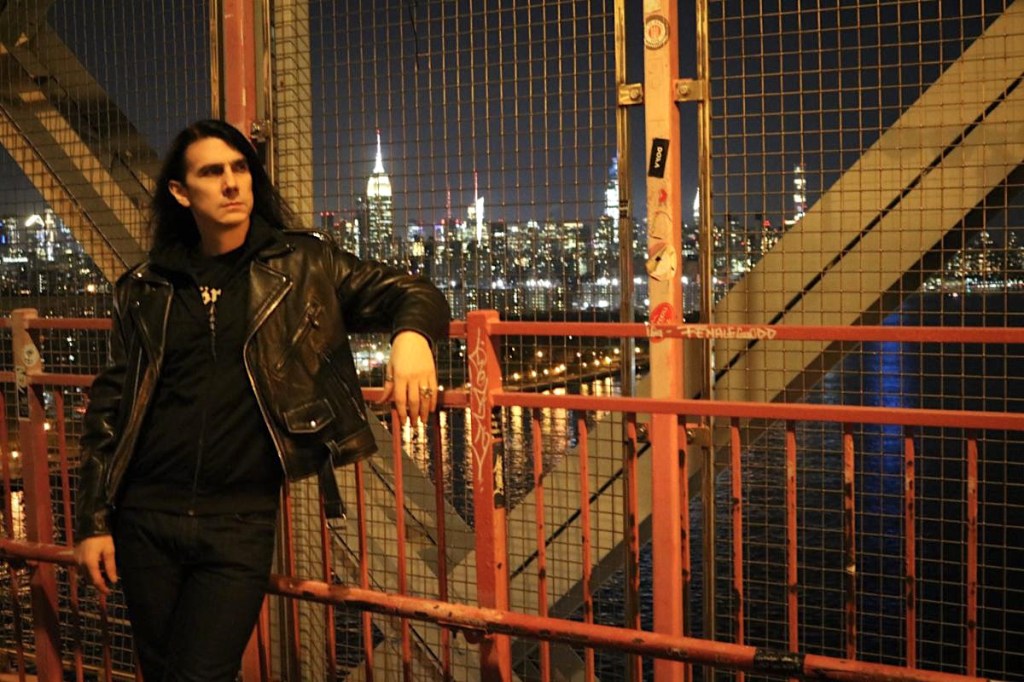

Chad Radford: “Chaos Magic”—the song and the video—have some very cinematic qualities to them. Have you considered moving into composing soundtracks for films?

I’ve thought about it, and I’ll probably end up doing it soon. I am currently developing a feature-length film—perhaps a series—a documentary about my father. He has a significant history, and I’ve been assessing how it will be structured. Aside from the music that he produced, I would create my own soundtrack around it. Our stories are kind of parallel. Any story about him includes me, especially towards the end of his life, when I was fighting his legal battles for him. I figure the incorporation of a noteworthy musical son of a noteworthy musical man would be an interesting part of the story.

Your father was a formidable country music mover and shaker. How did he and the music that he worked with influence you?

Probably the best lesson that my father ever taught me is that you don’t have to do anything the way anyone else does it. When I was in high school, everybody I knew was thinking about careers and getting married. One of my good friends during the ‘80s was Peter Steele from Type O Negative. We used to have conversations with him and Louie—I loved their music, and I would always say “you guys are going to be big.” But they were both adamant that they would never go on tour. They had union jobs with benefits, health insurance, and all that stuff. That was the life they had been taught, and once they had it, they coveted it and would never let it go. When Peter started Type O Negative, the band rule was you had to live on his block, to be close, and you had to agree to never go on tour. My mindset was never like that. I never once thought about my couch, having a home, getting a job. To a large extent, I’m still like that. I work in the film business as a camera operator. Most people think of that as a job, but I don’t. I am amazed every time I get a check. I show up to these places; there are like 80 other people there, all this amazing equipment, and actors. We assemble the scenes, shoot them, and then we go home. Then I get a check for it!

My dad also taught me that there’s a bigger world out there. He was a traveling man, and half of my life I didn’t know what he did for a living. I knew he did something, but he never went to a job, never had a schedule.

The thing I love about the film business is that it’s so similar to the music business: You’re around creative people, you get to be creative, but there aren’t four other guys trying to take credit for what you just did.

Just this morning, a Cro-Mags fan—someone who works in an archive in Washington, D.C.—sent me a stack of documents about my dad purchasing the Texas School Book Depository building. There’s one document that I’d never seen. It’s a commentary and observation of what happened the day of the auction for the building. You would think something like that would be very clinical, but the guy describes my father as this mysterious person who sat in the back, was elegantly dressed, and commanded the room. You knew something was going to happen with him before he started bidding. Then he won the auction, and the press swarmed him. It’s like reading a novel. For me—his son—I wasn’t surprised by the wording at all. I speak quite often with the producer of an HBO show about country music, called Tales From the Tour Bus, presented by Mike Judge. When they started doing interviews with people, talking about Johnny Paycheck, almost everybody they interviewed said you shouldn’t even do a movie about Paycheck. You should do it about Mayhew. He was way more interesting. So they reached out to me.

Is this the film project you mentioned working on earlier?

I am passively working on it. My father died in ‘09. His estate is still open, but we hope to close it this year. It’s still open because legal battles keep coming up. I fought lawsuits in Dallas against Texas oil millionaires. I fought lawsuits in Nashville against millionaire bootleggers, and I won both cases. When my father was at the end of his life, I basically took over his battles. After he passed away, I continued. It’s well worthwhile—I’m trying to protect his legacy.

I started speaking to Mike Judge’s producer about first doing a documentary series, which is just a natural for becoming a drama. So that’s where we are. I spoke with him about it a week ago; he’s looking for money backers. I don’t know which way it’ll go, but either way, I can’t work on it until after my father’s estate is closed. I don’t want to waive any flags and have people trying to sue me again.

Have you visited the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas?

I have. It’s an extraordinary thing. I didn’t realize the relevance of what my father did by saving the building until I was standing in Dealey Plaza. My father didn’t just save a building, he saved the déjà vu for millions of people. Literally, I came around the corner and was standing in Dealey Plaza, and my head started turning. I had been there a thousand times: There’s the grassy knoll, there’s the bridge where the cop was standing. There’s the fence where the dark man was supposedly standing with the rifle. Then my head panned over to the building, and my eyes went right to the sixth floor—the window on the right. I could’ve hit it with a baseball. Then I looked over my right shoulder and could see the limousine coming around the corner. That moment of déjà vu—from seeing the Zapruder film that we’ve all seen a thousand times. I relived that entire thing in 60 seconds. That’s history! My father recognized that saving that building was saving that moment. And that’s what my father did. He was a music man, he was an entertainer, and he recognized that 60 seconds as something that people should be able to experience. Meanwhile, the entire city of Dallas was trying to run him out of town.

Two other bidders wanted to tear it down. The City of Dallas wanted it torn down. They planned to bulldoze the grassy Knoll, reverse the traffic on the street out front, so it doesn’t look or feel the same way. Of course, after they ran my dad out of town, they put in a museum. The Dealey family, who owns Dealey Plaza, is a Texas society family. Their name is forever associated with the murder of a president, so they want that erased. Most people don’t know this, but the Dealey family owns The Dallas Morning News, who began a press campaign against my father, calling him a hillbilly, which couldn’t be further from the truth. All you have to do is read that document that was sent to me this morning. They described him as this striking, intelligent character. The Dallas Morning News portrayed my father as a hillbilly—someone who was going to open a chicken restaurant in the building called Kennedy Fried Chicken. It was absurd.

I’d never made the connection between the Dealey family that owns the paper and Dealey Plaza.

And a lot of people haven’t made the connection with the guy whom my father bought the building from—D.H. Byrd—whose lifelong friend and schoolmate was Lyndon Johnson. Who was the one person in the world who benefited from Kennedy’s assassination? Lyndon Johnson! The guy who owned the building he was shot from was Byrd?!?! Are you fucking kidding me?

Is the building still a part of your father’s estate?

No. The city of Dallas took it from him. It’s the most visited and most photographed building in Texas, even more than the Alamo. The city owes all of those tourists dollars to somebody they ran out of town. And my father’s name isn’t even on a plaque on the front of the building. Byrd’s name is on the front of it because he’s a Dallasite. It’s a good old boys club down there.

Read Parris Mayhew talks life after Cro-Mags, Aggros, and ‘Chaos Magic’ (Part 1)

If you have enjoyed reading this story, please consider making a donation to RadATL.